CEO's strategic overview

Dear shareholders,

By the time you start to read this letter (and please forgive the presumption that you do), its subject – 2011 – will be ancient history. Pearson will be more than one quarter of the way through the next year, and making plans for the next five.

Like us, you may be more concerned about the future than the past. But we all know that what has happened is the best guide to what might happen, so I’d like to give last year a little time in this report before I talk about our plans.

What happened in 2011?

After several tough years in the world economy, we began the year hoping for a change for the better. But it turned out to be more of the same: slow economic growth in the developed world; austerity measures taking their toll on spending by governments and consumers; a crisis of unemployment – especially among young people – that played its part in social unrest.

If that reads like a downbeat assessment of our world this past year, that’s how it felt. The wind was not in our sails. Even so, I’m anything but downbeat about the resilience and creativity Pearson’s people showed through those troubled and troubling waters.

Despite the gloom, they ground out another set of financial results to be proud of, and they achieved some goals that we believe will set us up for the future – and maybe even make the world a little better in the process.

You can see all the countable details in the charts on these pages, but to pick out a few of the high notes:

- Sales up 6%, and just shy of £5.9bn;

- Operating profits up 12%, to £942m;

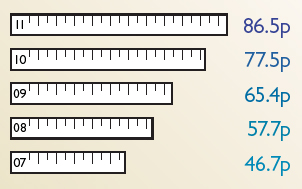

- Earnings per share also up 12%, to 86.5p;

- A proposed dividend increase of 9%, taking our full‑year payment to 42p; and

- An encouraging verdict from the stock market, which at year‑end had pushed our shares 20% higher than last year (and almost 90% higher over the past three years).

That share price ended the year just over £12, a ten‑ year high. And on most of those financial measures, we set all‑time highs for Pearson.

Key financial measures: five year record

Adjusted earning

per share pence

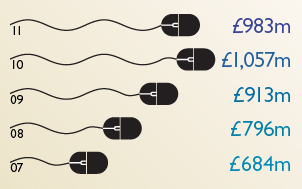

Operating cash

flow £m

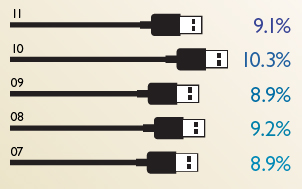

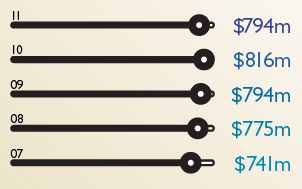

Adjusted operating

profit £m

Return

on invested

capital %

So, we can take one last look back at 2011 with some pride in a job well done. But we can’t spend any time congratulating ourselves. Another quick glance at the past tells us why.

Back in 2007, as the financial crisis was taking hold, the best consumer book company on the planet (that would be Penguin) published the memoirs of Alan Greenspan, the former chairman of the US Federal Reserve. In the financial crisis that followed, his legacy came under fire, but looking back, the title of his book was remarkably prescient. He called it The Age of Turbulence.

That’s a perfect description of what Pearson’s future holds, and what we have to plan for now. And there’s more than one kind of turbulence that’s going to require our vigilance and imagination:

Economic turbulence

The prospects for the world economy look dim for the short term. Any recovery from the 2008 financial crisis was faint and short‑lived. Europe is now ploughing through one urgent economic crisis after another; austerity measures around the over‑indebted world are having a deep impact, and growth appears to be slowing even in some emerging markets now.

Still, the big shifts in economic growth and power are accelerating. Developing economies are growing on average 3% points a year faster than the US. And if that gap continues, those so‑called ‘emerging’ markets will account for two‑thirds of the world’s output in less than 20 years. China may overtake America as the world’s largest economy within the next ten. That’s an exciting – and sobering – prospect for a company like ours that today makes around two‑thirds of its profits in America and just 2% in China.

Social turbulence

Economic turbulence generally builds to social upheaval. So those economic shifts are playing a part in protests across the Middle East, demonstrations in Western Europe and on Wall Street and riots in the UK.

Our flattening world is becoming more unequal. This past October, we reached a world population of seven billion people. More than half of them are living on $2 a day or less.

The world of work is one of the sources of profound disruption and anger (described by the Financial Times as ‘the din of inequity’).

Around the globe more than 200 million people are unemployed. The young have been hit especially hard. In America, the youth unemployment rate has increased almost 70% to 18% since 2007; in the UK the rate is even higher, at more than 20%. In rich OECD countries, one in five young people is out of work; in much of the Middle East it’s one in three; in parts of Southern Africa one in two.

And those who are ‘no‑longer‑young’ but still need to work can’t find it either because they don’t have the right skills. Creating new jobs – and helping people learn the skills that they’ll need to secure them and succeed – will be one of the most pressing priorities for governments around the world.

(I recognise the inherent dangers of raising such matters as someone in a very fortunate position whose remuneration is there for all to see somewhere in the pages of this report. But I’m convinced that large companies and the people who run them are going to have to understand and respond to these kinds of issues.)

Political turbulence

If we needed someone to tell us, former US President Bill Clinton did in the FT Magazine back in October: “Successful countries are ones where economic forces and government work together to raise job growth, lower unemployment, and narrow inequalities in income, health care and education.” But that kind of collaboration seems elusive right now.

In addition, our environment, both physical and social, is ever more political and ever more sensitive to political intervention. Managing those forces has come to be a requirement of every organisation. In our case that runs from consideration of media regulation and reform of education to copyright and intellectual property protection.

The public’s scepticism of financial institutions is also provoking more scepticism of companies in general, and especially of those that make a profit out of providing a public service, such as journalism or education. A climate of suspicion will be a critical challenge for a company that is large, global, successful and heavily dependent on the public’s trust and the public purse, as we are.

Technological turbulence

The death of Steve Jobs, the leader of Apple, was a moment to reflect on the remarkable technological changes in our times. At the start of his life, the silicon chip hadn’t been invented. By the end of it, only 56 years later, two billion people were using the internet and five billion were using mobile phones.

Not all of them by a long shot were using Apple devices, but that company did play a special role in the creation and growth of new consumer forms and technologies. It helped open fresh possibilities for many, including our company, and has made fundamental changes in what we do and how we do it. Those changes will only speed up.

What does that mean for our future?

So these are turbulent times for any company, but especially for one like ours. And this turbulence is not a freak storm at sea that will soon give way to calmer waters. This kind of disruption is our new reality. It’s the environment we have made our plans around for the next five years at least.

This environment doesn’t provoke us to change course, or to throw our strategy overboard. We think it remains a sound fundamental strategy, one that has proven it can enable the company to prosper through good times and bad. (In 2006, before the financial crisis and the subsequent recession, our sales were £4.4bn. In 2011, still in a downturn, they were more than 30% higher – around £6bn. In that time, our profit rose from less than £600m to close to £950m and earnings per share from a little over 40p to about 86p).

But the outside environment has inspired us to move more quickly, to be more radical in our approach, to be more courageous. The areas we’ll be changing centre on themes that are familiar, but on which we’re either moving faster or taking a different approach.

Here's a summary of them:

1. Investment: We're an aggressive, long‑term investor in our businesses. This past year, we made some £0.5bn of organic investment: new learning programmes and technologies, new authors, taking our assets into new markets.

In addition, we have over the past five years invested £2.5bn in acquisitions, all of which have been additions or fill‑ins to build our existing business. Our very strong balance sheet - just £500m of net debt at the end of 2011 - allows us to contemplate more of the same, should we see good opportunities.

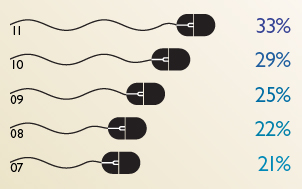

2. Technology: Today's Pearson is a technology company as much as we are a newspaper or book publishing company (though those don't go away in the digital age - they are more flexible). Digital businesses last year contributed about one‑third of our sales, or almost £2bn in total. Five years ago, they were 20%, about £720m. This represents a fundamental shift in our business, our culture and our growth opportunities.

3. Fast‑growing markets: For many years, Pearson was primarily an Anglo‑American company. Though we're still very much at home and working in those two countries, Pearson is now a truly international company with market‑leading businesses from China to India to Brazil to southern Africa. 'Emerging markets' last year added up to 11% of our sales - and 22% of our people (because we're generating rapid growth there and getting ready for more).

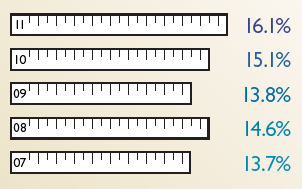

4. Efficiency and scale: While we've been growing, a feature of Pearson has long been steady efficiency gains also. Our margins reached an all‑time high of 16.1% this past year, and our cash generation was more than 100% of profits, as it has been for the last five years. Still, we see more to go for and more ways to go, especially as we accelerate our transition from traditional print‑based activities to digital and services models.

What I've talked about in this report are the themes that have brought us to where we are, and made us a more durable company. We think they, too, are durable. But that doesn't mean that our plans and programmes aren't both innovative and brave.

Our strategy

1. Long-term organic investment in content

Over the past five years, we have invested more than £4bn in our business: new education programmes; new and established authors for Penguin; the FT Group's journalism. We believe that this constant investment is critical to the quality and effectiveness of our products and that it has helped us gain share in many of our markets.

2. Digital products and services businesses

Our strategy is to add services to our content, usually enabled by technology, to make the content more useful, more personal and more valuable. These digital products and services businesses give us access to new, bigger and faster-growing markets. In 2011, our digital revenues were £2bn or 33% of Pearson's total sales.

3. International expansion

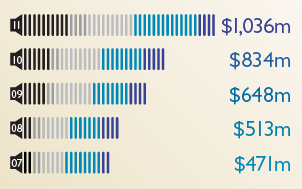

We are already present in more than 70 countries and we are investing to become a much larger global company, with particular emphasis on fast-growing markets in China, India, Africa and Latin America. In 2011, Pearson generated $1bn of revenue in developing markets for the first time. They now account for 11% of our total sales and 22% of our people.

4. Efficiency

Our investments in content, services and new geographic markets are fuelled by steady efficiency gains. Since 2007, our operating profit margins have increased from 13.7% to 16.1% and our ratio of average working capital to sales has improved from 20.1% to 16.9%.

Finally, as we encounter the future we've been preparing for, we will stand by some principles that have long been part of Pearson's DNA:

1. We want to follow our 'always

learning' motto inside as well as outside our company

- with our own people as well as with our customers. We want to

educate our workforce for the needs of today, and, more

importantly, for the needs they'll have throughout their working

lives - needs to change skills, to teach themselves, and to excel

rather than merely get by.

2. We want our work to be effective

in tackling some big problems. That means helping

people learn who have not had access to education; helping change

the face of business through new ways of learning and making

decisions; measuring ourselves by whether what we do is effective,

not whether it's used.

3. We want to be a company that has a

strong sense of social purpose (helping people make

progress in their lives through learning) and high standards of

ethical behaviour (which we summarise in Pearson's values: brave,

imaginative and decent).

As we strive to achieve these goals, we want our shareholders to

know and understand our direction. I hope you are enthused enough

about it to support us into this future that we've planned and

practiced for and now are taking head‑on.

Thank you for the support you've given us up to now.

Marjorie Scardino, Chief executive